For the second year in a row, the US has surpassed 25,000 whooping cough cases — another sign of the risks of falling vaccination levels, reports BritPanorama.

Commonly referred to as the “100-day cough,” whooping cough, or pertussis, commences with cold-like symptoms, including runny nose, fever, or a cough that can escalate into prolonged coughing fits lasting weeks or months, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In its second phase, a characteristic “whoop” sound may accompany the cough.

This bacterial infection can lead to severe illness or even death, especially among young children. Approximately one in three babies under the age of one who contracts whooping cough will require hospitalisation. Experts, however, believe much of the disease remains unrecognized and underreported, as stated by the CDC.

The CDC reported nearly 28,000 cases this year, a marked increase following last year’s peak of 35,493 cases. In contrast, only 7,063 cases were recorded one year earlier, in 2023.

The last time the figures were similarly elevated was 2014, when 32,971 cases were documented. Thirteen deaths from pertussis have occurred in the US this year, most of which involved infants under one year old.

This surge in whooping cough is not confined to the United States. The Pan American Health Organization, which serves as the World Health Organization’s office for the Americas, reported a significant increase in global cases. In 2024, WHO recorded 977,000 cases of pertussis, a five-fold rise from 2023.

Dr. Scott Roberts, an associate medical director for infection prevention at the Yale School of Medicine, attributes the rise in cases in the US to declining vaccination rates and the loss of population immunity exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic. “I worry vaccine hesitancy is playing a role. This is a vaccine-preventable illness, and any decline in vaccine rates will lead to increases in pertussis,” he noted.

Vaccines prevent whooping cough

The CDC recommends routine diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTaP) vaccinations for all infants and children under seven, beginning with a five-dose series starting at two months of age. Children who receive all five doses of the DTaP vaccine on schedule enjoy 98% protection from illness within the year following the final dose. However, about 70% of children remain fully protected five years after their last dose, according to the CDC.

Adults and adolescents are advised to obtain a Td or Tdap booster every ten years from the age of 11 or 12, with Roberts recommending that the Tdap version, which includes pertussis protection, should be preferred.

“Last year, we had a lot of college outbreaks. Many individuals complete their childhood vaccine series but do not receive the booster series,” Roberts explained. He noted that these outbreaks often occurred among students who had lost their immunity and were living in environments where the disease spread easily.

The return to shared indoor spaces post-pandemic may also have contributed to this increase, according to Dr. Roberts. He remarked that limited exposure to routine pathogens during the pandemic created a situation where a greater number of people are exposed to the whooping cough pathogen simultaneously. “I wonder if there is some degree of loss of population immunity that we’re still recovering from. Perhaps things will stabilize over the next few years,” he added.

Moreover, the Pan American Health Organization’s epidemiological update reveals that vaccination coverage for the first and third doses of Tdap in the Americas region fell to its lowest levels in two decades during the Covid-19 pandemic. In 2021, coverage rates stood at 87% for the first dose and 81% for the third.

Roberts underscores the critical importance of pertussis vaccinations for children and pregnant women. The CDC recommends a Tdap booster for expectant mothers between weeks 27 and 36 of pregnancy, regardless of their prior vaccination history. When pregnant women receive the vaccine, they develop antibodies against pertussis, which are transmitted to their babies through the placenta, ensuring some immunity at birth.

However, maternal antibodies decline within a few months, highlighting the necessity for children to complete the DTaP vaccine series.

Whooping cough symptoms and treatment

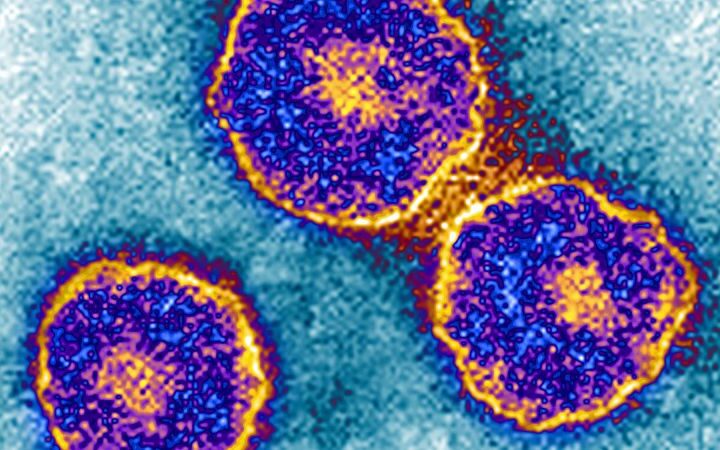

Whooping cough differs from the flu, Covid-19, and the common cold, being caused by a bacterium rather than a virus, although initial symptoms can appear similar. Dr. Shira Doron, chief infection control officer for Tufts Medicine, explains that the illness, caused by Bordetella pertussis, has distinct features. “Even though it can look like a viral respiratory infection, it’s actually a bacterial infection,” she notes.

As the illness progresses, individuals may experience the characteristic whoop when gasping for breath between coughing fits, typically appearing one to two weeks into the infection. Severe coughing can result in post-tussive vomiting — vomiting that occurs when coughing or immediately after. Doron recommends seeking medical advice if the cough worsens significantly, particularly if accompanied by vomiting or the characteristic whooping sound.

These severe symptoms arise from airway damage inflicted by the bacterial toxin. Antibiotics represent the primary treatment for whooping cough. When administered early, antibiotics can mitigate contagiousness and “break the chain of transmission,” although they do not alter the illness’s overall course.

Due to challenges in accessing pertussis rapid tests at clinics, healthcare providers often prescribe antibiotics based on patient symptoms. A common approach is to administer a five-day course of azithromycin, known as a Z-pak, which can effectively eliminate the bacteria in most circumstances.

Children and infants face the highest risk of severe illness, and certain symptoms should prompt immediate medical intervention. Signs of respiratory distress, such as difficulty breathing or a bluish tint to a baby’s skin, require urgent care. Infants are particularly vulnerable given their developing respiratory and immune systems, but severe cases are rare among vaccinated children.

States, counties urge residents to protect themselves

On Monday, health officials in South Carolina advised residents to ensure they are current on vaccinations amid a “concerning uptick” in cases of measles, whooping cough, and chickenpox.

Dr. Linda Bell, South Carolina’s state epidemiologist, attributed the unfortunate rise in these diseases to declining vaccination coverage in the region, which affects the broader state. “This trend is both preventable and reversible. Vaccines are one of the most effective tools we have for protecting our communities. When people choose not to vaccinate, outbreaks become more probable,” she stated.

Local health departments nationwide report declining vaccination rates. Dr. Raynard Washington, director of Mecklenburg County Public Health in North Carolina, noted an increase from one or two annual whooping cough cases to 68 in 2024, with 48 recorded by October 2025. Most cases are among children who are not up to date with their vaccinations, often clustered in communities where families delay or decline vaccines. “It does put more people in those neighborhoods at risk,” he remarked.

Concerns extend to older adults, given their more vulnerable immune systems. He suggests that older adults consult their healthcare providers about protection measures. In addition, Dr. Phil Huang, director of Dallas County Health and Human Services in Texas, reported escalating cases, with 40 in 2023, 160 in 2024, and at least 195 in 2025.

Data from the Texas Department of State Health Services indicates that kindergarten vaccination rates for pertussis fell from nearly 94% in the 2023–24 school year to below 90% the following year. Huang emphasized that the best measure parents can take is to ensure their children are fully vaccinated: “That’s the best protection that we can do.”

In addition, Roberts encouraged families to stay informed through local public health department websites about nearby cases, which may impact how doctors approach cold or flu-like symptoms. “If parents are concerned or the symptoms don’t improve after a couple of weeks, that’s a good time to consult a doctor,” he advised.