The shifting foreign-policy stances of the Poland and Hungary are creating a significant internal challenge for NATO’s eastern strategy, as one former close partner adopts divergent priorities.

Historical alignment and recent unraveling

Poland and Hungary joined NATO simultaneously on 12 March 1999, marking their joint pivot toward Western security structures. From that point until the early 2020s, their political relationship was largely constructive, including shared stances in the European Parliament and on EU budget and recovery-fund negotiations. Yet since the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, their strategic paths have markedly diverged.

Divergent responses to Russia’s aggression

Since 2022, Poland has taken a consistent, pro-Ukrainian posture — boosting military support, welcoming NATO reinforcement, and aggressively seeking to reduce Russian influence. In contrast, Hungary under Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has adopted rhetoric and policies more accommodating of Moscow, prompting public criticism from Poland’s leadership.

Energy reliance and strategic calculus

Energy policy has become a key fault line. Poland moved early to diversify gas supplies and launched its Baltic Pipe import from Norway in October 2022, aiming to minimise dependence on Russian energy. Hungary, by contrast, has deepened its dependence through agreements with Russia’s nuclear corporation and refused to engage in a full oil and gas decoupling—the choice naturally influencing its alignment on defence and sanctions decisions.

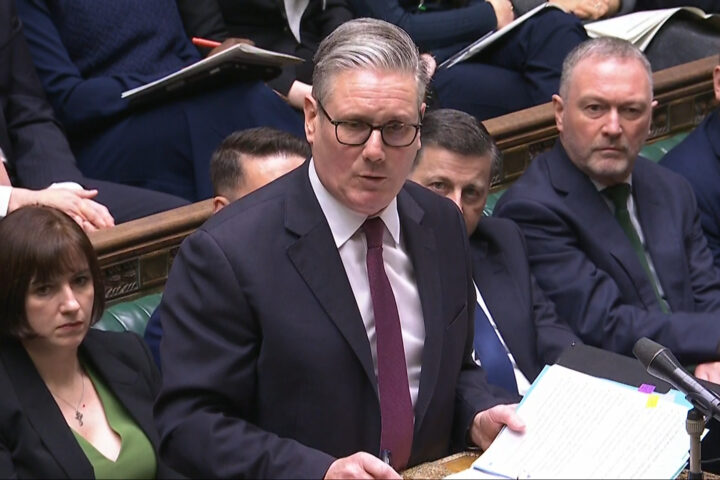

Personal diplomacy and symbolic gestures

Orbán’s frequent meetings with Vladimir Putin — both official and informal — project a channel of communication with Moscow that many in Warsaw regard as signalling a special status for Hungary within the alliance. Meanwhile, Budapest’s political discourse increasingly veers revisionist, reviving grievances around the 1920 Treaty of Trianon and deploying the imagery of a “Greater Hungary” during public appearances, including a scarf-map worn by Orbán at a sports event showing territory beyond current borders.

Implications for alliance cohesion and regional security

Hungary’s stance poses multiple interlinked risks for NATO’s eastern flank. First, its frequent use of vetoes and delays weakens bloc-level sanction and defence policies, potentially extending conflict duration and increasing pressure on Poland’s border regions. Second, by maintaining heavy dependence on Russian energy, Hungary undermines regional resilience and narrows strategic options for Central-Eastern Europe. Third, a NATO member having special ties with Moscow while accessing alliance intelligence threatens trust and operational solidarity. Finally, the revival of revisionist rhetoric in Hungary threatens the inviolability of borders—a foundational principle for Poland and broader regional stability.

Warsaw’s strategic imperative

For Poland, the situation is no longer bilateral: Budapest’s stance represents a structural challenge to NATO’s deterrence architecture and Central-Eastern cohesion. Warsaw faces the difficult task of both managing a regional ally-turning-systemic risk and preserving the broader alliance’s credibility on its eastern frontier.

Poland’s leadership therefore must communicate the gravity of the divergence and mobilise other allies for stronger internal discipline. Hungary should not simply be categorised as a “difficult partner” but rather understood as an actor whose strategic choices are reshaping the alliance’s eastern posture. In an era when deterrence and cohesion are paramount, this internal asymmetry may prove the alliance’s most serious vulnerability unless addressed.