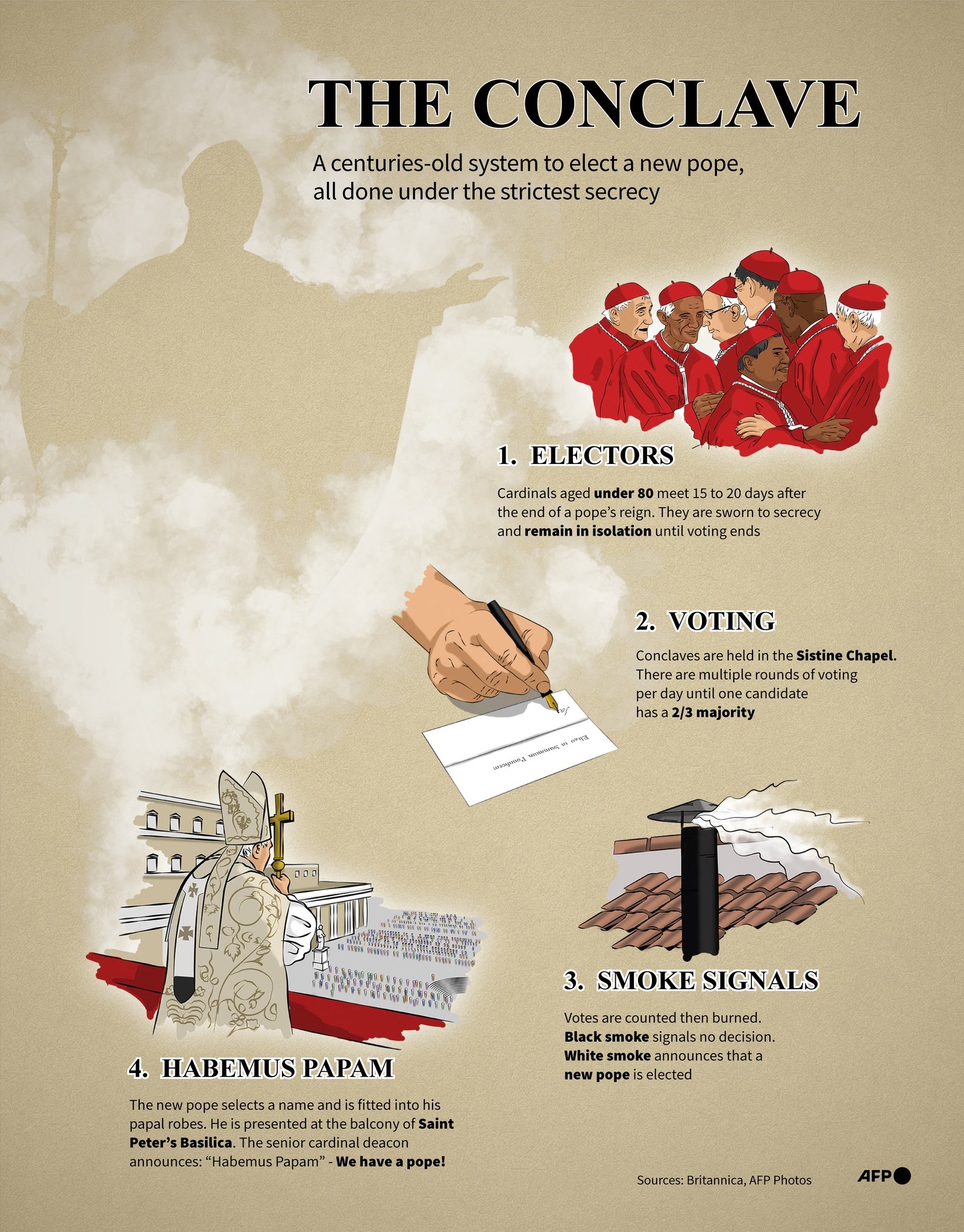

Under Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, cardinals from around the world will meet this week to begin the process of electing a new leader of the Catholic Church after Pope Francis’s death.

Dating back to the Middle Ages, the gathering, known as a conclave, has an air of mystery about it, as all participants are sworn to secrecy for life.

The word conclave comes from the Latin for “with key”, a reference to the lockdown imposed on cardinals during the process.

The deliberations of a conclave are held in strictest secrecy on pain of instant excommunication. Smartphones and any internet access are off-limits and cardinals cannot read newspapers, listen to the radio or watch TV.

Any contact with the outside world is banned, unless for “grave and urgent reasons”, which need to be confirmed by a panel of four peers.

Electing a new pope

The conclave will begin on Wednesday 7 May and last until a new pontiff is elected.

Meetings in advance of the conclave discuss the “qualities that the new pontiff must possess” and the most pressing Church challenges.

These include “evangelisation, the relationship with other faiths (and) the issue of abuse”, the Vatican said.

The longest conclave to date took almost three years, but modern gatherings are usually a matter of days.

Both Francis and his predecessor, Benedict XVI, were elected after two days of voting.

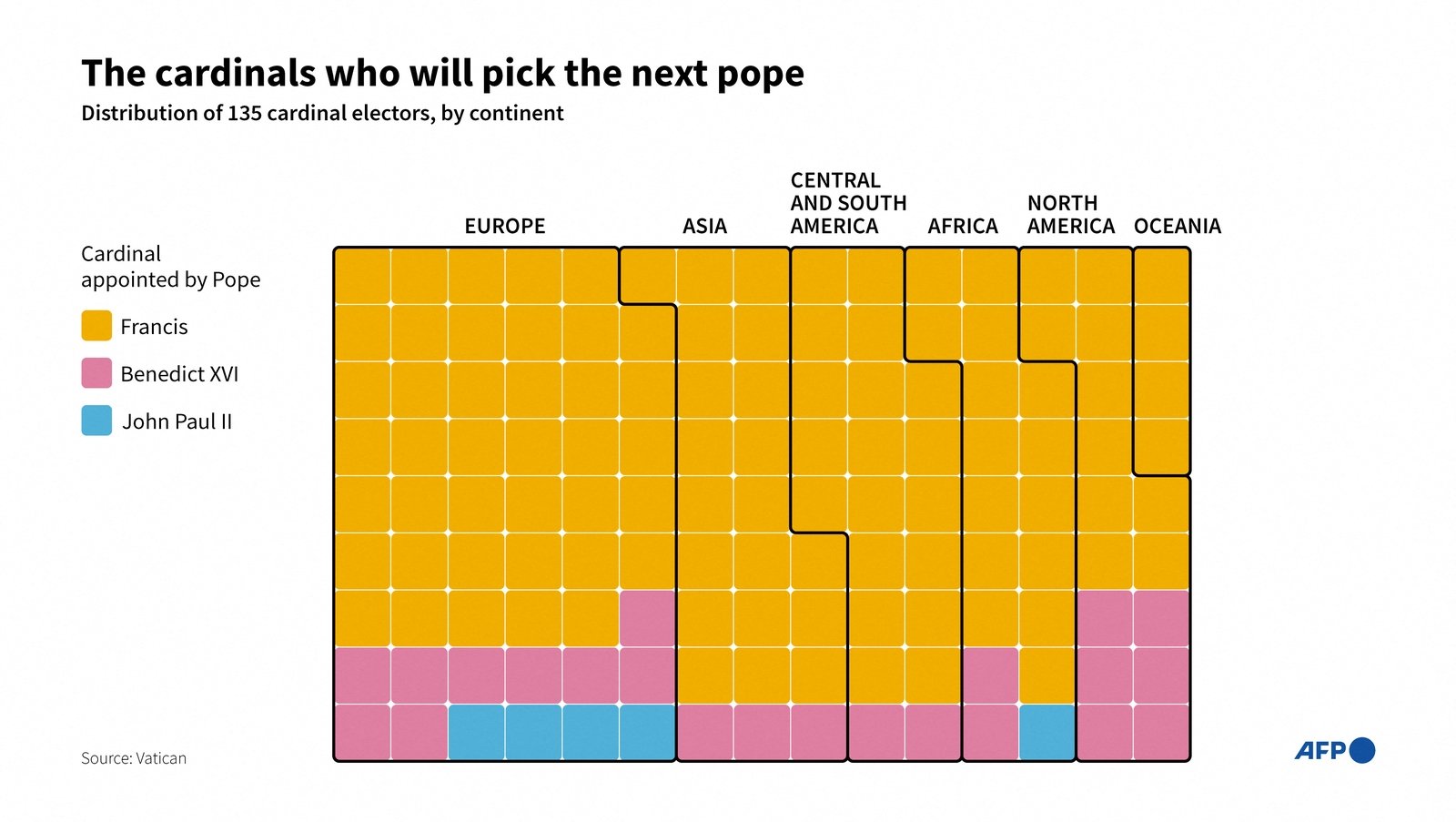

The cardinals who pick the pope

About 133 of the Church’s 252 cardinals are expected to take part in the conclave, as only those aged under 80 are eligible to vote for a new pope.

A cardinal (from the Latin “cardinalis” or principal) is a high dignitary of the Catholic Church chosen by the pope to assist him in his government.

The main dicasteries – the Holy See equivalent of government ministries – are, for the most part, headed by cardinals.

Their exact title is Cardinal of the Holy Roman Church.

Gathered in the College of Cardinals, presided over by a dean – currently the 91-year-old Italian Giovanni Battista Re – they form the top echelon of the Catholic Church.

Cardinal being a title and not a function, many of them are bishops of dioceses around the world, while others, who hold positions in the Curia, the Vatican’s government, live in Rome.

Most of the cardinals allowed to vote were appointed by the late Pope Francis – around 80%.

They hail from all corners of the globe, with many from under-represented regions.

But Europe still has the largest number, with 53 cardinals.

It compares to 27 cardinal-electors from Asia and Oceania, 21 from South and Central America, 16 from North America and 18 from Africa, according to the Vatican.

Italy is the most represented nation with 17 electors.

The United States has 10, Brazil seven and France five.

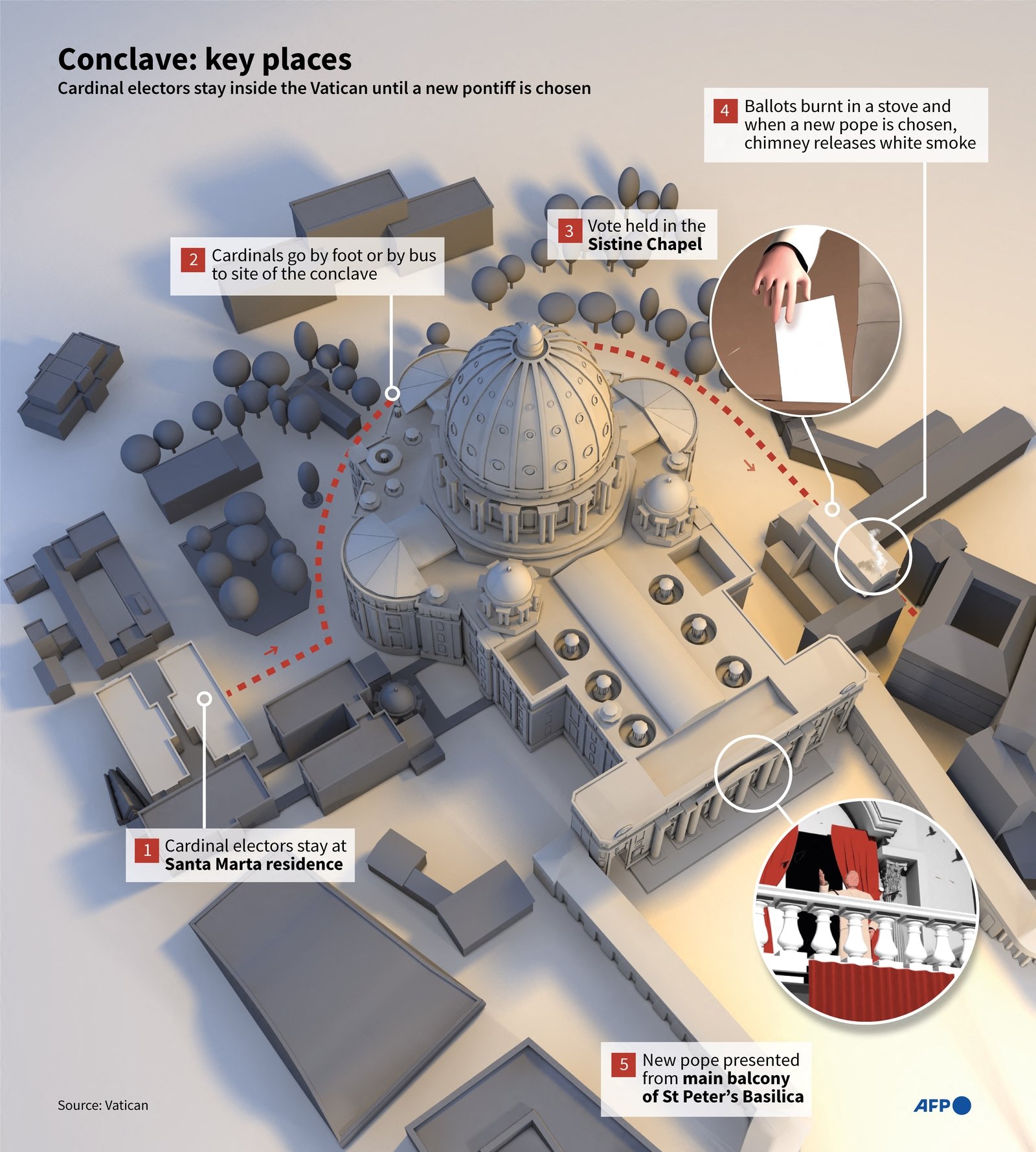

Backdrops to the daily rituals

From the Sistine Chapel to St Peter’s Square, the locations where the election of Francis’s successor will play out in the coming days are part of a cultural heritage.

The cardinals will move into Santa Marta guesthouse and stay until they have elected a new pope.

In centuries past, the cardinals slept in corridors and rooms of the Apostolic Palace itself.

St Peter’s Basilica

Cardinals will celebrate a special mass in this landmark of Roman Catholicism before the start of the conclave.

Following the mass, the Princes of the Church will walk in procession to the Sistine Chapel singing the hymn “Veni Creator Spiritus” (“Come Creator Spirit”) in Latin.

The basilica, one of the largest churches in the world, is a jewel of Renaissance architecture and contains the tomb of St Peter – the first pope.

Sistine Chapel

Every morning during the conclave, the cardinals will head 500 metres, either on foot or in minibuses with blacked-out windows, from Santa Marta guesthouse to the Sistine Chapel.

Situated inside the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican, this 15th-century chapel is world renowned for its spectacular frescoes by Michelangelo.

A special stove has been installed in the chapel where the cardinals’ ballots are burnt after each round of voting during the conclave, until a new pope is picked.

Black smoke indicates that the required majority for a new pope has not been found.

White smoke means that there is a new leader of the Catholic world.

St Peter’s Square

Architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini, in the 17th century, designed the famous Vatican plaza, which has a 4,000-year-old Egyptian obelisk at its centre.

The famous marble colonnades – four columns deep – are arranged in an elliptical shape.

Tens of thousands of people are expected to gather in the square to await the election of the pope.

He will appear to the world for the first time on the main balcony of the basilica’s facade, and he will then deliver his first blessing.

‘Extra omnes’ – the conclave begins

On the morning of the conclave, the cardinal electors take part in a mass in St Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican.

In the afternoon, wearing their choir dress of a scarlet cassock, white rochet and scarlet mozetta (short cape), the cardinals gather in the Pauline Chapel of the Apostolic Palace and invoke the assistance of the Holy Spirit as they make their choice.

They then proceed to the Sistine Chapel, where the election will be held and which will have been swept for secret recording devices.

The cardinal electors take an oath promising that, if elected, they will conduct the role faithfully – and again vowing secrecy.

The master of ceremonies gives the order “Extra omnes”, meaning “everyone out”, and all those not permitted to vote leave the Sistine Chapel.

Continuity or change?

“These cardinals don’t know one another very well,” says John L Allen Jr, author of numerous books on the Vatican.

“This could be a prescription for a protracted conclave because it would be difficult to form consensus among people who don’t have a strong sense of where one another is coming from.

“But the flip side of that, is it could also be a prescription for a very short conclave.

“A large number of cardinals who feel sort of lost and adrift may simply play follow the leader, looking to sort of well-known, well-established figures who have been around a long time and putting themselves in their hands.”

He added: “There is an extraordinarily powerful incentive built into the system not to let this go too long.

“Because the last thing the cardinals want is to give the world the impression that they are divided and that the Church is adrift and in crisis.”

“Every conclave to some extent shapes up as a referendum on the papacy that’s just ended – do we want to keep it going and therefore find somebody who stands in continuity with the previous pope, or do we want to make a change?”

“In 2005, the vote was overwhelmingly for continuity. That’s how you got to Pope Benedict XVI, who had been John Paul’s right-hand man, in four ballots.

“And in 2013, the vote was overwhelmingly for change. That’s how you got to Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Argentina in five ballots.

“This time, I think it is far less clear which of those two options is going to prevail. I think instead, you’re likely to get a mix of continuity and change.”

Three years of conclave

The longest conclave in history lasted almost three years following the death of Clement IV in November 1268, held in the papal palace at Viterbo, near Rome.

From late 1269 the cardinals allowed themselves to be locked in to try to reach a decision, and by June 1270, frustrated locals tore the roof off in a bid to speed things along.

They were apparently inspired by a quip by an English cardinal that without the roof, the Holy Spirit could descend unhindered.

Teobaldo Visconti became Pope Gregory X in September 1271.

But the longest conclave in more recent times was that of 1831, which elected Gregory XVI after more than 50 days.

The longest of the 20th century, lasted only five days (14 ballots) when Pius XI was elected in 1922.

In 2005, Benedict XVI was elected in just two days (four ballots) and Francis in 2013 also in two days (five ballots).

The secrecy of the vote

The masters of ceremonies distribute ballots to the cardinal electors, with lots drawn to select three to serve as “scrutineers”, three “infirmarii” to collect the votes of cardinals who fall ill, and three “revisers” who check the ballot counting by the scrutineers.

Cardinals are given rectangular ballots inscribed at the top with the words “Eligo in Summum Pontificem” (“I elect as supreme pontiff”) and a blank space underneath.

Electors write down the name of their choice for future pope, preferably in handwriting which cannot be identified as their own, and fold the ballot paper twice.

Each cardinal takes turns to walk to the altar, carrying his vote in the air so that it can be clearly seen.

He says aloud the following oath: “I call as my witness Christ the Lord, who will be my judge, that my vote is given to the one who before God I think should be elected.”

The electors place their folded paper on a plate, which is used to tip the ballots into a silver urn on the altar, in front of scrutineers. They then bow and return to their seats.

Those cardinals unable to walk to the altar hand their vote to a scrutineer, who drops it in the urn for them.

If there are cardinals who are too sick to vote, the infirmarii collect their ballot papers from their bedsides – and may even write the name of the candidate for them if necessary – in a special locked urn and bring them back to the chapel.

Once all ballots are collected, scrutineers shake the urn to mix the votes, transfer them into a second container to check there are the same number of ballots as electors, and begin counting them.

Two scrutineers note down the names while a third reads them aloud, piercing the ballots with a needle through the word “Eligo” and stringing them together. The revisers then double-check that the scrutineers have not made any mistakes.

If no one has secured two-thirds of the votes, there is no winner and the electors move straight on to a second round.

The burning of the ballots

Cardinals hold four ballots a day – two in the morning and two in the afternoon – until one candidate wins two-thirds of the votes.

At the end of each session, the ballots are burned in a special stove.

Destroyed too are any handwritten notes made by the cardinals.

With the addition of chemicals, the stove’s chimney stack emits black smoke if no one has been elected, or white smoke if there is a new pope.

The Catholic world waits to see if the smoke is black or white.

If no new pope is elected after three days, cardinals take a break with a day of prayer, reflection and dialogue.

If after another seven ballots there is no winner, there is another day of pause.

If the cardinals reach a fourth pause with no result, they can agree to vote only on the two most popular candidates, with the winner requiring a clear majority.

Any single Catholic adult male can be elected pope, although in practice it is almost always one of the cardinals.

‘Habemus Papam’

White smoke appears from the chimney when a new pope is elected.

The masters of ceremonies and other non electors are brought back into the Sistine Chapel and the Dean of Cardinals asks the person: “Do you accept your canonical election as Supreme Pontiff?”

As soon as he gives his consent, he becomes pope.

He is then asked what name he has chosen as pontiff.

The new pope then retreats to a room known as the Room of Tears – a tiny room adjoining the Sistine Chapel.

The tradition was that the new pope sat and cried for the big responsibility in Vatican City, Vatican.

There, he puts on the papal garb – three sizes of which have been left out in advance – and emerges in front of the crowds in St Peter’s Square.

The new leader of the world’s 1.4 billion Catholics appears on a balcony overlooking the square as a senior cardinal cries: “Habemus Papam” (We have a Pope)!