A female wild wolf on the central coast of British Columbia was recorded pulling a crab trap from the ocean to access the bait, potentially marking the first documented example of tool use by a wolf, reports BritPanorama.

The traps were set by the Heiltsuk (Haíɫzaqv) Nation as part of an environmental stewardship strategy aimed at addressing the invasive European green crab, which threatens local ecosystems. The program is designed to protect the region’s biodiversity, showcasing Indigenous efforts to manage wildlife sustainably.

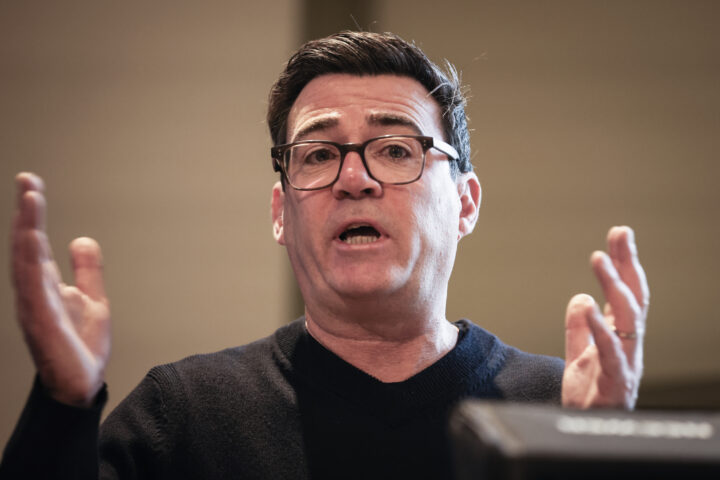

Kyle Artelle, an assistant professor at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry and a co-author of a related study, noted that damage to the traps suggested involvement from wildlife. “The traps were starting to get damaged, and the damage did look like it could have been a bear or a wolf,” he explained.

Researchers set up motion-triggered cameras to determine which species were interacting with the traps. Contrary to expectations of seeing otters or seals, footage revealed the wolf swimming ashore with a buoy in her mouth. After dropping the buoy, she manipulated a line attached to a trap, eventually hauling it toward the shore before breaking open a container that held herring bait.

Artelle expressed surprise at the observations. “We were amazed. It was not what we were expecting,” he said, emphasizing the intelligence displayed by the wolf. This behavior highlights the capacity for problem-solving in wildlife, suggesting that wolves are capable of complex actions in pursuit of food.

Focused action, not play

The researchers documented another interaction between a different wolf and a crab trap, though this recording did not confirm whether the second wolf was able to extract the canister. Artelle hypothesized that these behaviors might stem from the wolves’ observations of humans deploying the traps or from encounters with traps in shallower waters.

Artelle remarked on the cognitive complexity required for the wolf’s actions, noting, “It’s a sequence of behaviors that ultimately gets her towards that goal. It’s problem-solving, and it’s problem-solving exactly the way humans do it.” He compared this intelligent action to what a human would do when attempting to access a similar trap.

While the extent of this behavior among the wolf population remains unclear, Artelle stated this specific instance suggests a potential for learned behaviors in wolves within a context where they face fewer human-related threats. “The question that it raises for us is: Might this behavior develop here because the wolves aren’t so preoccupied with having to look over their shoulders?”

Tool use or not?

The classification of such behaviors as tool use has sparked debate in the scientific community. Ever since Jane Goodall first documented tool use in chimpanzees, researchers have recognized this capability across several species. Artelle believes the wolf’s action qualifies as tool use but acknowledges differing interpretations of what constitutes a tool.

“Some definitions say tool use means the use of an object external to yourself to achieve a goal, which this clearly is,” he said. However, he also pointed out that other definitions require modification of the tool. “She didn’t tie the line to the crab trap. It was already built for her.”

Marc Bekoff, an animal behavior expert, echoed Artelle’s view, suggesting that understanding whether similar behaviors appear culturally within wolf populations could be a future research avenue. However, others argue for more stringent criteria regarding the definition of tool use. Bradley Smith, a senior lecturer at Central Queensland University, opined that the wolf’s actions do not meet traditional definitions of tool use but should not undermine the significance of the observation as an example of problem-solving.

Alex Kacelnik, an emeritus professor at the University of Oxford, emphasized the importance of understanding how such behaviors are learned rather than being tied up in definitions. “This is a beautiful set of observations, and the authors do a great job in addressing its possible significance,” he stated.

The study detailing these findings was published on November 17 in the journal Ecology and Evolution.