Burned bone fragments found in northern Malawi have revealed the oldest cremation pyre ever discovered in Africa — and unearthed new mysteries that may be hard to solve, reports BritPanorama.

Researchers believe that hunter-gatherers cremated the body of a woman approximately 9,500 years ago, according to their study published Thursday in the journal Science Advances.

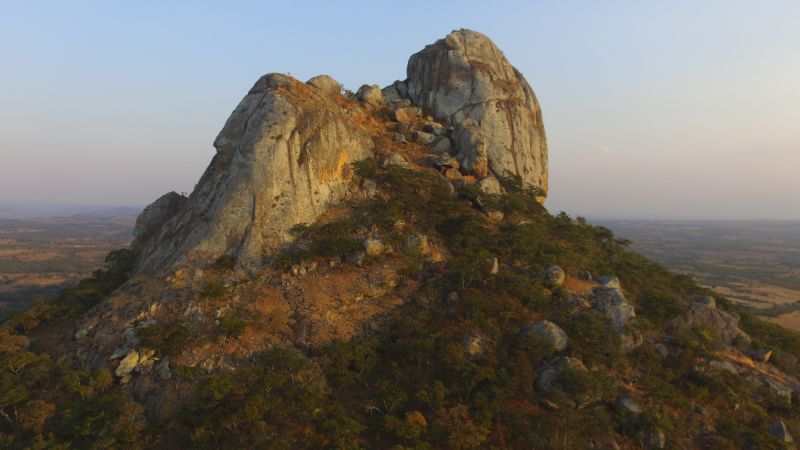

The pyre and human remains were unearthed near the base of Mount Hora, a prominent granite mountain that rises sharply above an otherwise flat plain. Forensic analysis indicates that the bone fragments, predominantly from arm and leg bones, belonged to a woman aged between 18 and 60 who stood just under 5 feet tall.

The site, named Hora 1, is situated beneath a natural boulder overhang large enough to shelter around 30 people. Initially excavated in the 1950s, it was identified as a hunter-gatherer burial ground. Recent research, initiated in 2016, has shown that humans began residing at the site approximately 21,000 years ago, with burials occurring between 8,000 and 16,000 years ago.

However, the discovery of the bone fragments marks the only cremation recorded at the site, which is particularly unusual given that such practices were rare during that era, researchers noted.

“Cremation is very rare among ancient and modern hunter-gatherers, at least partially because pyres require a huge amount of labor, time, and fuel to transform a body into fragmented and calcined bone and ash,” said lead author Jessica Cerezo-Román, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Oklahoma.

This striking discovery sheds light on the complex and largely unknown funerary practices of African hunter-gatherers and raises the question of why such an effort was expended for the cremation of just one individual.

A spectacular effort

Excavations at the site between 2016 and 2019 unveiled a large ash mound, roughly the size of a queen bed, containing two clusters of human bone fragments displaying burn patterns.

Prior discoveries of cremations in Africa have been traced to pastoral Neolithic herders from about 3,500 years ago or to later food-producing societies with higher population densities, making this finding particularly unexpected.

“While we were excavating the pyre feature, there was an ongoing argument about how this could not possibly be a hunter-gatherer mortuary practice, and how there was no way it could be more than a couple thousand years old,” said study coauthor Dr. Jessica Thompson, assistant professor in the department of anthropology at Yale University. “When the radiocarbon dates came back, they blew us away.”

The analysis also indicated that great care was exercised during the cremation process.

Evidence of fungus and termites in the wood suggests that around 70 pounds (30 kilograms) of dry deadwood were collected for the pyre, indicating a considerable investment of time and effort, according to study coauthor Dr. Elizabeth Sawchuk, curator of human evolution at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

Moreover, the fire reached temperatures exceeding 932 degrees Fahrenheit (500 degrees Celsius), with the size of the ash mound implying that the blaze may have burned for several hours to several days, necessitating active refueling throughout the process.

Flaked stone tools were also discovered on the pyre, suggesting that these pointed stones were added as funerary objects during the cremation.

“Cremation is something that we in the modern Western world don’t often give a second thought to, because it’s done by professionals in closed environments, but for other societies it would’ve been an intense visceral experience to build, light, and bury a funeral pyre,” said Lorraine Hu, manager of human histories and cultures at the National Geographic Society.

Missing pieces

Cut marks on the bones indicate that people actively participated in the cremation process by removing some of the woman’s flesh. However, the idea that the woman was a victim of cannibalism was dismissed due to differences between these cut marks and patterns found on animal bones from the site.

Notably, there were no fragments of teeth or skull bones in the pyre, leading researchers to believe that the head may have been removed before the burning. While this may appear gruesome, Cerezo-Román posits that complex rituals of remembrance may have underpinned this act.

“There is growing evidence among ancient hunter-gatherers in Malawi for mortuary rituals that include posthumous removal, curation, and secondary reburial of body parts, perhaps as tokens,” she explained.

But why was this woman cremated while others were buried intact? Other complete burials have been documented at the site, suggesting she may have warranted special treatment.

Little is known about her life beyond her low mobility, but her bone structure indicates she likely used her arms more in her daily activities compared to other hunter-gatherers interred at the site.

“While we can never truly know the motivations of ancient peoples, it seems likely that unusual circumstances in her life and/or death prompted this kind of unusual cultural treatment,” Sawchuk remarked. “Whether it was for positive or negative reasons is a big question mark.”

Recovering lost cultural history

Malawi was under British colonial rule when Hora 1 was first excavated in 1950, at a time when archaeology often resembled treasure hunting. Skeletons of both genders were discovered, but without dating, which left the rest of the site treated as largely mysterious.

The excavations conducted between 2016 and 2019 were part of the Malawi Ancient Lifeways and Peoples Project, aimed at collecting missing cultural evidence of the people who inhabited the site for 21,000 years, leaving behind beads, animal bones, and tools. Since then, more burials, ancient human DNA, and tiny bone fragments have been uncovered.

Recent evidence suggests that these hunter-gatherers practiced the removal of small bone fragments to serve as tokens of memory, perhaps marking significant locations.

Archaeological findings indicate that 700 years prior to the cremation, large fires were set at the same location, and 500 years later, large fires were lit atop the pyre, although no cremated remains were found.

Mount Hora may have served as a natural monument or site for cultural rituals, an idea supported by the evidence of fire use over generations.

“It felt like people had come back, within community memory of what had happened there, and reenacted the ritual all over again,” Thompson said. “The fires were so unnecessarily large to just be campfires, which are usually economical in size. This indicates that the event retained significance for these people long after the cremation itself.”

The recent discoveries at Hora 1 illustrate the sophisticated cultural behaviors of hunter-gatherers long before the advent of urbanization and agriculture, indicating a high level of social complexity.

“What is so interesting about this case is that it shows that hunter-gatherers living nearly 10,000 years ago had the capacity for and skills to cremate their dead, but generally chose not to do so,” Sawchuk added.

The difficulty in understanding hunter-gatherer societies is attributed to their lack of extensive settlements. Further studies of natural formations that may have provided shelter or a reevaluation of collections in museums are essential to uncover the diversity of their lives.

“Ancient African hunter-gatherers have historically been treated as uniform, when in fact they likely possessed as much cultural diversity in beliefs and practices as any other groups,” Thompson concluded.