As the Gate Theatre’s acclaimed revival of Brian Friel’s play returns to Dublin’s 3Olympia this July, Thomas Conway explores the enduring appeal of the Donegal playwright’s work.

‘a fox knows many things but a hedgehog knows one big thing’ – Archilochus

Brian Friel may have aspired to the condition of the fox, always experimenting, always pitching in new directions, always breaking the rules. But he seemed equally inclined towards that of the hedgehog, circling the same obsessions around memory and imagination, around what is perceived and what is actual, around the treacheries involved in shoring up our identities on images of the past that are so little to be trusted. His remarkable output of twenty-four original plays and eight adaptations are distinguished for their stylistic variety and restless innovation, and yet they are also unified by recurring obsessions and motifs.

In what does Friel’s signature abide? Noting his attention to language as the vehicle for drama gets us some of the way there. We hear Friel testify to this absolute commitment to language at the darkest moment of his struggle with the composition of Translations, as recorded in his journal: ‘…the play has to do with language and only language. …if it becomes overwhelmed by the political element it is lost.’ The redundancy of language seduces Friel too, to judge by so many of his plays, Dancing at Lughnasa among them, that go beyond language in their final moments: ‘Dancing as if language no longer existed because words were no longer necessary.’ Also with Friel, the musical and rhythmical aspects matter more in the structuring than more expected qualities such as plot. As such, while he takes on political themes and public issues, he exercises a primary concern with qualities of language and style, with musical shape, with expressing the inner ebb and flow of thought and emotion.

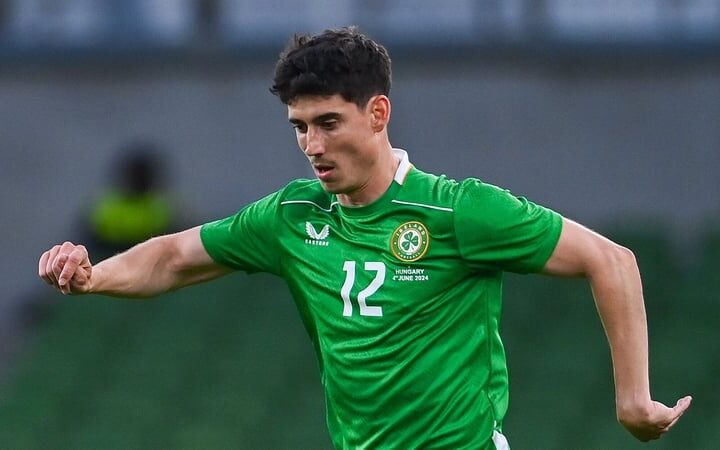

Friel’s Philadelphia, Here I Come! at Cork Playhouse in 2021

Friel’s obsessive return to the fraught boundaries between memory and imagination, between remembering things as they were and as we wish them to have been, between recording the past and making things up, is exemplified in his reliance on the allegorical setting of Ballybeg for many of his most enduring dramas. Ballybeg is itself recognisably a place in history and a realm of the imagination. How do we reckon with the fact that fourteen of Friel’s plays have Ballybeg (or Baile Beag, as he called it in Irish) as a setting or key point of reference?

We need only dig a little deeper to see correspondences between his two most enduring plays set in Ballybeg for evidence of Friel’s wider obsessions: Philadelphia, Here I Come! and Dancing at Lughnasa, plays written twenty-five years apart, yet seemingly built on a shared bedrock of memory and myth. Why else does Friel insist on a day’s outing in a little blue rowing boat on a remote uplands lake near Ballybeg for both plays? Gar remembers fishing with his father from such a boat in Philadelphia, Here I Come! Rose gives an account of a tryst with Danny Bradley in a boat of the same description in Dancing at Lughnasa. Why else does Friel give Gar (from the earlier play) and Michael (from the later play) four childless Mundy aunts? Why does he retain the names of Agnes and Rose for two of those aunts?

Memory’s betrayals can only be explored, it seems, by means of such a common stock of images and their correspondences; here we see Friel delve into aspects of his own family history and its mythologies. The Mundy sisters, we are told, are modelled on his aunts, and the tensions between fathers and sons explored across so many of the plays reflects aspects of a strained relationship between Friel and his own headmaster father. What partly distinguishes Friel’s work, then, is the attention to the deeply personal that ultimately yields a view on the wholly universal: Friel works from his own particular historical co-ordinates and perspectives with such linguistic dexterity and scrupulous honesty that it resonates with everyone’s experience.

This quest to state things precisely on his own terms also explains one of Friel’s more idiosyncratic features. Friel’s plays are distinguished by the softening he exerts on their edges only to draw an audience into the hardest of human truths. (For many Irish playwrights, the trajectory is so often the reverse, a spiky exterior hides a sentimental core.) Friel seems to work in a whimsical register initially, only to ensnare us with a devastating consequence, one that knocks us off balance and leaves us re-evaluating the pattern we thought was unfolding. Such moments not only reveal character in a new light; the actions leading up to the reversal need to be rethought. These elusive endings invite us not merely to contemplate the future but to question everything that has gone before. The plays thus begin again in the mind of the audience the moment the curtain descends on the stage.

(This may owe something to Friel’s experience as a teacher: as the best teachers do, he leads us by simple steps steadily and stealthily to ever more complex perspectives on a shared dilemma. By the time the audience gains a purchase on the complexity at the heart of the action it feels itself hovering in mid-air, where language is both self-sufficient and no longer serves; it is caught in a moment of suspension that precedes a fall from innocence into experience.)

Friel’s risk-taking is never more apparent than in the theatrical conceits with which he launches the action—the theatrical sleights of hand that sets the language itself in motion. In Philadelphia, Here I Come! a central character is shadowed by an alter ego; the audience are privileged to hear what Gar alone hears from that private self; the audience also, however, looks Gar’s alter ego in the eye, something that Gar never manages to do. In Translations a community speaks Irish but the audience hears English; this community can neither comprehend nor be comprehended by the colonists who seek to govern their lives, but they can by the discerning audience. In Dancing at Lughnasa, a child is addressed by his aunts but this child is never embodied by a child-actor—rather, the child’s dialogue is spoken by the adult narrator without conceding in any way to a child’s vocal mannerisms.

This attention to language is matched by Friel’s scrupulous tracking of psychological movements in the characters.

These conceits are Friel’s self-imposed challenges that he meets head-on in the act of composition; the playing out of the logic of these conceits oftentimes gives the plays their dynamism and shape. They are Friel’s stylistic responses to the one constant in the worlds he depicts: the reticence and social constraints on language to which the plays bear witness. Nobody in Friel’s world is able to speak her or his mind to another character; however, somehow, by these sleights of hand, the audience are vouchsafed these confidences. What a shock it is, then, to discover that Gar’s father as likely has his own alter ego shouting into his ear, keeping him awake, shaking his resolve, and his own bank of memories in which he once had a loving connection with his son. Who would have guessed that ‘old Screwballs’ has his own inner voice goading him to speak and sabotaging his feeble attempts?

The actions are invariably positioned within seismic societal change—where one way of life is being overtaken by another. It is here the plays find their characteristic tone or atmosphere. The central characters are seldom defiant or resigned, but wistful and conflicted about finding themselves unable to take sides. They neither oppose change nor promote it outright; they neither defend themselves against change nor look to guide it or others through it. InTranslations, Hugh concedes to teach Maire English only to reveal the quisling he has proven to be. In Dancing at Lughnasa Michael tells us that he finds his missing aunts when it is too late to intervene on their behalf. In Philadelphia, Here I Come! Gar fails to decide why he is leaving, but he knows he must leave.

These proxies for Friel often presume to cast a backward glance at changes that may yet still be in train. They look to language as a means to get above these changes and to survey them whole, even as they are part of the flux; they discover in language an inadequacy that never quite gets these changes into proper focus. These characters find in language both their single best resource and something that fails them. Dramatic form, as Friel would reveal, is better than all other literary forms for speaking not only through but around language, to its strengths and its incapacities; drama needs words, the very best words, but it also abandons them. Friel achieves a near impossible balancing act between these two conditions in ways that testify to the utmost care he brought to the labour of writing.

This attention to language is matched by Friel’s scrupulous tracking of psychological movements in the characters. Here we frequently see a pattern whereby a character’s taciturnity and brooding silences are broken by sudden outbursts of zeal and articulacy that are then of no consequence and resolve again into brooding silence. These outbursts are absorbed into some greater historical movement and disappear. The march of history is given a location and a form precisely in Friel’s mapping of the failures of the individual to make any distinctive mark against it.

How is it that Friel should achieve a vantage point where he can see from above whilst being in the midst of the change himself? It seems that whatever the style the fox in him chooses to exploit, the hedgehog in him re-encounters the tidal force of history pulling him into its current. The fox’s freedom and the hedgehog’s servitude are always at odds, always held in tension, always yielding to new forms developing around obsessive constants.

Even in that journal he wrote during the composition of Translations we hear the conflict play out in neither’s favour. The fox pulls him in one direction: ‘The play must concern itself only with the dark and private places of individual souls.’ The hedgehog pulls him in the other: ‘But it is a political play—how can that be avoided?’ Maybe it is the abundance of forms and styles within something so recognisably Friel’s that accounts for the exhilaration we experience in each encounter with his plays. However uneasy and provisional is each balancing act, some measure of what we all need to survive in the face of change is somehow to be found in, and indeed, around these plays.

Thomas Conway is the New Work Manager for the Gate Theatre. Dancing at Lughnasa is at the 3Olympia Theatre, Dublin, from 1st – 26th July 2025.